Lately, I have been receiving a lot of questions concerning Viking hairstyles, all inspired by Travis Fimmel’s fancy haircut in The History Channel’s Vikings. A recent blog post Ragnar Lothbrok’s Viking Style by Nancy Marie Brown inspired me to delve deeper into the matter. The present article will quote the original sources on Norse male hairstyles during the Viking Age, then it will give a translation and interpretation of each, and finally it will offer a few thoughts on whether Ragnar’s haircut in Vikings looks historically accurate.

Lately, I have been receiving a lot of questions concerning Viking hairstyles, all inspired by Travis Fimmel’s fancy haircut in The History Channel’s Vikings. A recent blog post Ragnar Lothbrok’s Viking Style by Nancy Marie Brown inspired me to delve deeper into the matter. The present article will quote the original sources on Norse male hairstyles during the Viking Age, then it will give a translation and interpretation of each, and finally it will offer a few thoughts on whether Ragnar’s haircut in Vikings looks historically accurate.

We have two witnesses as for the hair of the Norsemen in early Middle Ages:

- Leo the Deacon (born ca. 950). In his History, written about AD 989—992, Leo describes how John I Tzimiskes (Byzantine emperor) met Sviatoslav (prince of Kievan Rus) in July 971. Whether Leo himself was present at the meeting, is unclear.

- Ælfric of Eynsham (also born ca. 950). In his Letter to Edward, written about AD 1000, partly in rhythmical alliterative prose, Ælfric speaks about English people who adopt heathen Danish customs, which he considers to be shameful.

Till the present day, there is only one edition of the original Greek text of Leo the Deacon’s History: Leonis Diaconi Caloënsis Historiae Libri Decem: Et Liber de Velitatione Bellica Nicephori Augusti. Bonnae: Impensis Ed. Weberi, 1828. The Greek text was edited and translated into Latin by Carl Benedict Hase (a new critical edition was prepared in the 1970s by N. Panagiotakes but it was never published). On pp. 167—168 of this 1828 Bonn edition we read the following description of Sviatoslav:

Καὶ ὁ Σφενδοσθλάβος δὲ ἧκεν ἐπί τινος Σκυθικοῦ ἀκαθίου παραπλέων τὸν ποταμὸν, τῆς κώπης ἡμμένος καὶ σὺν τοῖς ἑτέροις ἐρέττων, ὡς εἷς λοιπῶν. τὴν δὲ ἰδέαν τοιόσδε τις ἦν· τὴν ἡλικίαν μεμετρημένος, οὔτε εἰς ὓψος παρὰ τοῦ εἰκότος ἠρμένος, οὔτε εἰς βραχύτητα συντελλόμενος· δασεῖς τὰς ὀφρῦς, γλαυκοὺς ἔχων τοὺς ὀφθαλμοὺς, τὴν ῥῖνα σιμὸς, ἐψιλωμένος τὸν πώγωνα, τῷ ἄνωθεν χείλει δασείαις καὶ εἰς μῆκος καθειμέναις θριξὶ κομῶν περιττῶς. τὴν δὲ κεφαλὴν πάνυ ἐψίλωτο· παρὰ δὲ θάτερον μέρος αὐτῆς βόστρυχος ἀπῃώρητο, τὴν τοῦ γένους ἐμφαίνων εὐγένειαν· εὐπαγὴς τὸν αὐχένα, τὰ στέρνα εὐρὺς, καὶ τὴν ἄλλην διάπλασιν εὖ μάλα διηρθρωμένος· σκυθρωπὸς δέ τις καὶ θηριώδης ἐδείκνυτο. θατέρῳ δὲ τῶν ὤτων χρύσειον ἐξῆπτο ἐνώτιον, δυσὶ μαργάροις κεκοσμημένον, ἄνθρακος λίθου αὐτοῖς μεσιτεύοντος. ἐσθὴς τούτῳ λευκὴ, οὐδέν τι τῶν ἑτέρων ὑπαλλάττουσα ἢ καθαρότητι. ὀλίγα γοῦν ἄττα περὶ διαλλαγῆς τῷ βασιλεῖ ἐντυχὼν, παρὰ τὸν ζυγὸν τοῦ ἀκατίου ἐφεζόμενος, ἀπηλλάττετο.

The fragment of text highlighted in red is the most important as for the hairstyle, but no less controversial as well. In a recent English edition of Leo the Deacon’s work it is translated as follows: “He shaved his head completely, except for a lock of hair that hung down on one side” (Byzantine Military Expansion in the Tenth Century: The History of Leo the Deacon. Introduction, Translation and Annotation by Alice-Mary Talbot and Denis F. Sullivan with the assistance of George T. Dennis and Stamatina McGrath. Dumbarton Oaks, 2005, p. 199).

The problematic word here is θάτερον, which, quite paradoxically, can be translated both “on one side” and “on both sides”. C. B. Hase in his first Latin translation preferred the latter variant: “Capite item erat admodum glaber; nisi quod ad utrumque latus cincinnus dependebat” (p. 157). Steven Runciman (A history of the First Bulgarian Empire. London: G. Bell & Sons, 1930, p. 213) when he sums up the description of Sviatoslav by Leo the Deacon, supports it: “From his shaven head fell two long locks”.

My translation of the passage in question is as follows:

Sviatoslav came by the river, in a Scythian boat, wielding an oar and rowing with his companions, like one of them. To speak about his appearance, he was of medium height, neither tall nor short. He had bushy brows, light blue eyes, turned-up nose, thin beard (variant: bare chin), and thick, too lengthy moustache. His head was shaven clean. Some of his hair fell on one side (variant: on both sides) of his head, showing the high rank of his kin. He had a solid back of the head and a broad chest. His other limbs were proportionate. He looked gloomy and wild. He wore a golden ear-ring in his ear: it was decorated with two pearls and a carbuncle between them. He had white clothes that differed from those of his companions only by its cleanness. He talked to the monarch briefly about the truce, seated on the bench for oarsmen, and then departed.

In what ways can this text be helpful to determine what the Viking Age Norse hairstyles were? There are a few problems to be mentioned:

- Prince Sviatoslav represented the third generation of Varangians in Russia. His father Igor and grandfather Rurik had Scandinavian names (Old Norse Ingvar and Rørik respectively), whereas his own name was of Slavic origin (composed of two roots meaning ‘holy’ and ‘glory’). More than a century elapsed between AD 862, when Rurik first came to Russia, and 971, when John I Tzimiskes met Sviatoslav. How much of the Norse tradition did the prince actually keep? Is it appropriate to call his hairstyle (whatever it was) Viking, Norse or even Varangian?

- About 20 years elapsed between the above-mentioned meeting and the time of Leo the Deacon’s book’s composition. It is not known whether he was present at the meeting personally or just retold the story.

- For Leo, Sviatoslav represented Scythians. Leo’s description of the Russian prince has some parallels with Priscus’ description of Attila, which he could use as a model. Can we trust the minor details of his story such as hairstyle?

- The actual meaning of the passage on Sviatoslav’s hair is unclear: it might be interpreted as saying about a single lock of hair or two locks on both sides of the shaven head.

Taking into account all that, the witness of the Byzantine author seems to be rather shaky. Now to his Anglo-Saxon contemporary. Ælfric’s text was published several times. Check the excellent work of Professor Mary Clayton: Letter to Brother Edward: A Student Edition. Old English Newsletter, 40 (3), pp. 31—46.

Ic secge eac ðe, broðor Eadweard, nu ðu me þyses bæde, þæt ge doð unrihtlice þæt ge ða Engliscan þeawas forlætað þe eowre fæderas heoldon and hæðenra manna þeawas lufiað þe eow ðæs lifes neunnon, and mid ðam geswuteliað þæt ge forseoð eower cynn and eowre yldran mid þam unþeawum, þonne ge him on teonan tysliað eow on Denisc, ableredum hneccan and ablendum eagum.

The text highlighted in red describes the hairstyle. Like Leo the Deacon’s description, it is not unproblematic: the word ablered is a hapax legomenon, that is the word, which is attested only once in the whole of the Old English literature. It seems to be connected with the word blere ‘bald’ and its suggested meaning is ‘bare of hair’.

My translation of Ælfric’s text is as follows:

I also say to you, brother Edward, since you asked me about it, that you do something unrighteous abandoning the English customs, which your fathers held, and loving the customs of the heathens who did not give life to you, showing that you despise your race and your elders by the vices such as dressing yourself as a Dane, with bare neck and blinded eyes.

The Bayeux embroidery depicting the events of AD 1064—1066, which led to the Norman conquest of England, yields an interesting witness as for the bare necks. Norman warriors look like the backs of their heads are indeed shaven, which may endorse the interpretation of the word ablered in Ælfric. However, one should keep in mind that what later became Normandy was founded by Rollo in AD 911, a century and a half before the Battle of Hastings. The same question as the one regarding Sviatoslav arouses: how much of the original Norse tradition could these people keep by 1066? At the same time, Ælfric’s testimony, if correctly interpreted, is the most valuable: he expressly points to the fact that the customs he describes are Denisc. People who were the source and the model for such practices believed they were Danes and were described as such by the Anglo-Saxons. But what exactly is Ælfric talking about? He mentions dressing, not hair (tyslian is a rare verb meaning ‘to dress’) and then points to the necks that are “bare of hair” (ablered). What is the logical connection between dressing and hair? It is to note as well that a bare neck is not the same as a bare back of the head. Any short haircut leaves the neck bare, one does not need to shave the back of the head for that.

Do all the three witnesses — Leo the Deacon, Ælfric of Eynsham and the anonymous authors of the Bayeux embroidery — represent one and the same tradition? My opinion is that they actually may do so. If we accept the “two locks” interpretation of Leo’s text, we easily bring it into correlation with Ælfric: indeed, if one shaves much of the neck, the rest of the hair may look like two long locks of hair that fall on both sides of the head.

However, Leo might misunderstand what others told about Sviatoslav, Ælfric’s ablered may mean something different or be a scribe’s error and the Bayeux warriors’ hairstyles may have no connection with the previous two sources. But even such a hypercritical analysis leaves us with a confirmation that at least Normans did have bare backs of the heads in the 1070s, when the Bayeux embroidery was created.

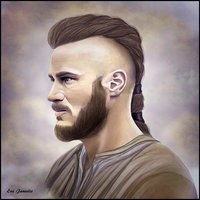

In view of the sources considered above, does Ragnar’s hairstyle in The History Channel’s Vikings TV series look historical? I don’t believe so. His neck is not “bare”, which is a prerequisite for any interpretation of the sources: whether Sviatoslav had a single lock of hair or two of them, his hair did not fell on the back of his head (note that Leo characterizes the back of his head as “solid”, which also confirms that it was shaven). Ragnar’s hair is braided, which also seems to be unlikely. At the same time, Ragnar’s son Bjorn and many other characters of the series have haircuts that correspond to the Norman tradition: the backs of their heads are shaven (even though the fringe is not long enough to state that their eyes are “blinded”).

Michael Hirst, the creator of Vikings, is reported to say: “In the end, how the f*** do you know what the Vikings looked like!”. I agree. We don’t know it for sure. Like much of the historical research, it’s all about suggestions.

Images: Ragnar, by EvaJaneelis. All rights reserved. Bayeux embroidery, fragment, by Urban. Used under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported Licence.

Interestingly enough, in Ukraine, the traditional haircut for men is exactly the same as described by Leo wore by King Sviatoslav – thick long moustache and clean shaved head with a hair lock falling from one side. Google “oseledets”, many people in Ukraine wear this even now. It appears that after the fall of Kievan Rus to Mongol and Lithuanian invaders, the Ukrainian cossacks preserved this ancient tradition. It’s hard to tell whether this has Norse or Slavic roots, but it’s a fascinating case nevertheless.

I think it worth noting that you did not mention the abundance of combs that existed in that time. I am certainly no expert, but I have read much and seen many examples of prized combs viking and ancient Scandinavian peoples had. I suppose the argument could be made that it was for women’s hair, but honestly I don’t buy that. I am fairly sure many of the men were buried and found with their hygiene kits which included combs. This would at the very least indicate a long enough beard to bother, if nothing else, but I would think it likely they would use it for their hair. A certain length of hair stops really needing a comb I would think. That’s just my two cents.

The Roman soldiers shaved so the enemy could not grab their beard and cut their head off. In military conflict, hair gets in the way. Helmets fit better with short hair. What the folks did back on the farm, is another matter.

It is not quite truth. Longer hair was wanted under helmets, they worked as layer of protection and also it is much more confortable to wear it. Just try one of these steel medieval helmets. When fighter was not rich enough to have helmet, no hair was prefered as you said.

As shown on the Bayeux tapestry they shaved their head except on the top, and that was padding for their helmet. (Nothing to do with the sun!) And it probably looked cooler than a bald nut.

No doubt that people came up with different styles but that big fat braid is stupid as a helmet would have been unsteady on it and enemies could have grabbed it.

Long beards are also a fantasy. Vikings were clean shaven.

There is evidence suggesting otherwise. On Gotlandic picture stones, men and warriors are pictured with pointy chins suggesting beards. There are also beards on male figurines from the viking age in Scandinavia and Iceland as well as on wood carvings on the Oseberg ship.

If beard is fantasy why all sculptures and engraving showing viking man with beard?

Just like today there’s plenty of different styles. Some were bearded. Some weren’t. We can’t draw absolutes on most things back then anyways.

There’s a 2000 year old tapestry that shows a Scythian on a horse (without stirrups) and he’s clean shaven except for a GIANT handlebar mustache. No joke

https://images.app.goo.gl/e76dURHgxRVVzfLg8

You may also want to look into the tribal hairstyle of the Frisians, to the south of Denmark.

The sources are later (Bartholomeus anglicus. Not sure if i spell that correctly) but still speak of high-shaven heads. Shaven from tyhe back as well as the sides. the higher the shave, the higher the status of the man.

We have immages from 1100 or earlier in the church of Westerwijtwerd which depicts this hairstyle exactly.

There is another source mentioning this hairstyle, but i forgot what that was.

the discription: Shaven very high from the back and the sides to only a single lok. In the case of the frisians, the lock was short and did not fall down the side of the head

I have always felt that do many things about how people might have looked, dressed or did whatever in past times is based off of only a couple sources and cannot possibly be representative of everyone from that time. Taking those 3 sources and trying to merge them together to come up with one look is probably a mistake. I would think that Vikings were individualistic to and extent just as we are. Maybe different Vikings shave different areas of their heads.

I have thought about hairstyle in practical terms. One is mentioned, cold. A bit of hair helps keeping warm. But raids happened mostly in good summer weather. Adapted to severe cold after winter shaving the head except on top would be a way of keeping cool, with the top being to prevent sunburn. I would suspect it would be seasonal.

Vikings mostly fought up close. I did some saber fencing and have a little sense for how this kind of battle would happen. In the real world with a shield and sword or axe, there would be a fair amount of grappling. Swordplay is movie nonsense. You get the hit or not. Its hard to block with a sword. And if you do, you are likely to harm your sword and have it break or notch. If it were me I’d want several knives handy and a few axes and the lightest shield I could manage.

The point being, I wouldn’t want a nice handhold on my head. Hair could be long enough to show but not to grab. That hairstyle shown looks fairly practical with hair forward acting to shade the eyes like a ballcap. It doesn’t look flopped over the eyes. That suggests that either hair was curly enough (unlikely) or some kind of pomade would hold it in place. There are lots of things to use for that, from grease to pitch and combinations of things. Hair treated that way would be less likely to have lice as well.

My interpretation of Viking history is that the started as farmers in a tough land. They began trading, in tbings like ivory and learned of wealth and also that gold and silver were valuable for trade. As population increased that put pressure on farming and trade. Raiding I suspect started out of ecomonic practical necessity. It also allowed creation of a better lifestyle for women back home.

Seasonal nature of the Viking hairstyle is an interesting idea. Thanks for sharing this.

Why do we assume out of all the tribes and peoples that we can determine from a few sources exactly how everyone looked? Why would they all have the same beards and hairstyles? They had trends and idols as we do now. They had there own ways of expressing their dominance through appearance the same as we do today. Most people wear a suit in an office, but they don’t wear the same suit.

Medieval people were much less inclined to innovation than modern people. One of the reasons why Norse settlement in Greenland died out was their obstinate wearing clothes they used to wear in a less harsh environment.

I’m from Ukraine, the territory that originally had located Kievian Rus.

We still have this traditional hair cut for those our boys and men who hold the cossacks’ tradition. This hairdo is called ‘oseledets’ (herring) :))))

You may google зачіска оселедець to visualize it.

Thank you, Olena, sounds interesting.

Vikings – The were all Danes.

They came from Scandinavia. Norway = ‘The northen way’ (by ship), Denmark: Scandinavian boarder to the south, (Mark = border to the danes territory – Danevirke) Jylland, Sjælland, Skåne, Lolland, Langeland and all the other islands between Jytland and Norway/Sweden, East- and west Götaland, and Svealand (that gave name to Sweden) And the all spoke the same language – Danish Tung -Danske tunge – Dönsk tunga

However, Irish annalists differentiated between White Foreigners, Norwegians (Finn-gaill), and Black Foreigners, Danes (Dubh-gaill).

Eh, there is plenty of argument on the Irish annalists that the differentiation was based not on Norwegians and Danes but based on time of arrival. Ie new vikings versus the old vikings…

Why were the Danes called “Black”? Is this a joke?

I believe I read once it was either due to the nature of their presence with the ‘white Danes’ being traders and the ‘black Danes’ being invaders or that it was the predominate hair colour of the respective ‘Danes’ with blonde being white and dark hair being black. Specifically that those from Norway were more likely dark haired and those from other parts of Scandinavia being more likely to be blonde. Probably more nuance to it though.

It could be color marking for cardinal directions. White, Black, Red, Yellow(Golden)/Blue/Green are common conventions for marking different cardinal directions and “center” – exact order might differ between groups. You can see them in used in Kyivian Ruthenia (Black Ruthenia, White Ruthenia, Red Ruthenia), you can see them used by steppe cultures (Golden Orde and other “color” Ordes) and I found some claims that Native Americans of both Americas also used these colors.

Viking is just a profession or activity, not ethnicity. Slavs were participating in viking activities too. Savic vikings were called for example “chąśnicy” in case of these from western Pomeranian region of present day Poland.