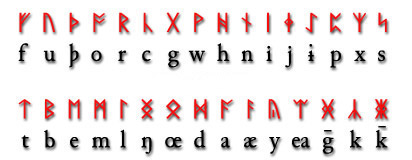

Futhorc is a system of runic writing used in Anglo-Saxon and Frisian inscriptions belonging to the 5th to 9th centuries. Already the word itself shows that Futhorc (as compared to Common Germanic Futhark) developed due to phonemic changes in the languages that it was designed to transcribe:

At first, both Old English and Old Frisian used a runic alphabet of 26 signs, adding two new runes in order to allow for reflecting the soundchanges in West Germanic languages known as Ingveonic changes. These included (but were not limited to): (a) nasalization, (b) fronting and (c) monophthongization:

(a) a > o before nasal consonant and a + n > ō before voiceless spirant;

(b) a > æ when not followed by a nasal consonant;

(c) Gmc. *ai > OE ā; Gmc. *au > OFris. ā.

A good example of these changes is the name Oswald, the first element of which (ōs-), due to nasalization, reflects the common Germanic *ans-, found in the name of the *ansuz rune. Where this single rune sufficed in Germanic, one now needed three runes: (1) for /æ/, which developed as a result of fronting; (2) for short /a/ not affected by fronting and for long /a:/, which developed due to monophthongization; (3) for short /o/ and long /o:/, which developed due to nasalization. In Futhorc the original *ansuz rune was used to cover the first option (æ) and received a new name æsc, ‘ash-tree’. To cover the second and third options, two new runes were invented, both on the basis of the *ansuz rune: āc, which seems to be a combination of a + i and ōs, which seems to be a combination of a + n. It is the new ōs rune that now took the fourth place in the system, wherefore the change of the name: Futhark > Futhorc. Whether or not the use of these two additional runes reflecting parallel linguistic changes both in Frisia and Anglo-Saxon England point to a period of ‘Anglo-Frisian’ unity is a disputed issue. Whatever the case, from the 7th century on English runic alphabet continued to develop independently, adding new signs. Listed above are 31 runes, which are found in the inscriptions. There are three more runes that occur only in manuscript listings and were probably invented by a medieval scholar or learned rune-master. These are runes ior for ‘io’, cweorþ for ‘q’ and stan for ’st’.

A special place among Anglo-Saxon Futhorc inscriptions belongs to the 8th century Ruthwell Cross with 320 runes, containing portions of the poem known as The Dream of the Rood preserved in the so-called Vercelli Book. No less remarkable are the Francis Casket and St. Cuthbert’s Coffin.

The transliteration of the oldest Anglo-Saxon runic inscriptions is given in bold Roman lower-case letters. However, for later ones a so called Dickins-Page system is often used, according to which the transliteration is given in s p a c e d letters within ’single’ quotation marks.

Hello. Thank you for this resource.

I’m trying to educate myself more on Anglo-Frisian Futhorc (which seems to be tricky – as there appears to be a fair bit of mis-information out there)! I am looking for more (real) information on the meaning of each rune / letter.

As an example, so many websites say things along the lines the following: that Laguz (‘l’ I think?) means water / sea, but also dreams, intuition, imagination etc. And Kenaz / Kaunaz (‘k’ I think, but this may be only in Futhark) means fire, torch, but also creativity, inspiration and knowledge.

Could you please give me an idea of whether this type of thing is accurate, or just some sort of fake mysticism that the modern world has put on the old language? Also, if it IS accurate, are there any texts or websites you could point me to with the accurate meanings of each rune (if there are multiple meanings for each rune – then all of them, as the web leads me to believe)?

Many thanks for any help you can give.

Fake mysticism.

I’m considering doing a wood sculpture with runes written on a post 6 to 8 inches wide, and 6 feet high. The inscription will be a phrase that repeats over and over: “world without end of the world without end of the world….” etc. Depending on the size of the runes a word like “without” or “world” may not fit on one line. I’ve looked at many examples of runic monuments online but I can’t tell whether of not if the carver ran out of space on a line, before completing the word, he continued the rest of the word on the next line, then indicated the end of the word with a period, i.e. withou

t . end.

If that’s the case its better for me since it gives me more freedom in sizing and placement. If not I’ll have to rethink the way I do it. Am I also correct in thinking that words were often or usually separated by dots?

thanks in advance

richard

Richard, words were sometimes separated by dots (two dots) or crosses. There were no stable rules for the division of words.

How would you write Woden? As in the Anglo Saxon god? Would it just be straight from the chart or did they use certain runes to indicate the accent ie the long O?

Jack, they used one and the same rune for both long and short o.

I’m trying to find which runes to transliterate my given name in. My surname is Germanic by way of Holland. So, I’m looking for a type that reflects that heritage. please & thank you.

Hello. Anglo-Saxon runes were used for Old English and Old Frisian. Frisians inhabited coastal parts of the Netherlands and Germany. So Anglo-Saxon runes may be a great choice.

Hi

In England would the two systems of Viking and Anglo Saxon runes have been used concurrently in the 9th and 10 th centuries and was there a time when British Vikings would have switched to Anglo Saxon or on gravestones or did they always use their own system.

Thanks Geoff

Hello Geoff. As far as I know, Vikings did not use Anglo-Saxon runes. They were not fit for their language.

Hello,

I am attempting to teach myself how to transcribe in Anglo-Saxon runes. By reading many books containing such examples and understandings of old translated to modern like RUNIC AND HEROIC POEMS OF THE OLD TEUTONIC PEOPLES I can translate the poems to modern English. I still find difficulty transcribing the results into Anglo-Saxon runes. This is because of the similarities and minor differances between the 24-runes of older Futhark and the 33 runes of Fuþorc.

I would like send you a simple text to transcribe (part of a Anglo Saxon poem) into Anglo-Saxon runes so that I have an example as to how it should appear correctly. I will leave the example below in both old and modern English and if you could email me with with the result that would be great. I would just like to get a better grip on it so I can transcribe properly. Thank you

Old: Yr byþ æþelinga and eorla gehwæs

wyn and wyrþmynd, byþ on wicge fæger,

fæstlic on færelde, fyrdgeatewa sum

Modern: Yr is a source of joy and honour

to every prince and knight;

it looks well on a horse and

is a reliable equipment for a journey

Hello Justin. Do you find any difficulty in following the chart above? It seems pretty intuitive, you simply substitute letters for runes as desribed.

Hello, I’m doing a bit of my own research on the Elder Futhark and Anglo-Saxon Futhork, and I’m a bit confused with the two. In “Reading the past runes” by R I Page, the English letter ‘j’ is the rune ‘Jera’, and in this book the Anglo-Saxon rune is depicted as a cross ‘x’ with a vertical stave running through the middle. But this is also the depiction of the rune ‘Ior’ in the Younger Futhork, which is a completely different sound (“io” as in “Helios”), with a completely different meaning, and your translation of the letter ‘j’ for the rune Jera is a diamond with a vertical stave running through it. So my question is: which is the true Anglo-Saxon depiction of the rune Jera?

I should mention the other book I’m using for cross-referencing is “The complete illustrated guide to runes” by Nigel Pennick.

Thanks in advance for your help!

Kind regards,

Jake

Hello Jake. First, we should not confound various types of runic alphabets. The word Futhork is usually applied to medieval runes, an alphabet of 27 runes based on the Younger Futhark set of 16 runes. The word Futhorc is usually applied to Anglo-Saxon runes. The word Futhark is applied to the Elder and the Younger Futhark.

In the Elder Futhark, Proto-Germanic /j/ was transcribed with the rune jera

In the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, Old English /j/ was transcribed with the rune gēr. On the actual artifacts it is consistently written

The lantern form appears in the manuscripts:

Where there is the lantern form for gēr, there is also a separate rune for ior, which is, then

In this case, it seems to be the bind rune of gyfu and is. It is not to be confounded with the Younger Futhark hagall rune, which looks the same.

Hello, thank you for getting back to me so quickly! I understand the evolution of the Elder and Younger Futharcs to the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc, and the role the phenomenon “sound-change” played regarding the phonetics of the runes, specifically in this case the rune Jera to Gēr.

If Gēr is written as a bind rune for Gyfu and Is on artifacts, could this be due to the fact that artifacts would be traded and sold and the meaning of Gyfu is to gift/exchange?

If that’s the case, then perhaps when it is written in manuscripts, as there’s no intention of an exchange, the lantern is used to avoid confusion for when ‘Ior’ is used?

As there are what I would call ‘natural bind runes’ which have occured through the evolution of runes, would I then be correct in understanding that if any and all runes can be put together, then runes have a homographic quality to them? So, depending on their usage in a word or ‘sentence’ (for want of a better description), it would be clear what a rune master would be conveying (i.e in english sow -is a pig, but you can sow seeds Or indeed like how the Japanese use their alphabet characters of sounds with a meaning in one word to apply to another)?

The more I read into the actual history of runes, I understand that there was great symbolic meaning as much as there was an aural meaning to them.

Also, I would like to know if the principle of not using the same rune twice in a word as would happen in the Elder Futharc, would still be applied in the Anglo-Saxon futhorc? For example, if I wanted to write the English name Helene, the phonetic translation to fit the rune sounds would become Helena, but if you were to write this name in runes, would you write the rune Ehwaz twice (I inderstand that Halgall is in the form of two verticle staves connected with a diagonal double barrel, and not as you have illustrated with the Younger Futharc to avoid confusiuon!)?

And finally my name, being a derivitive of Jacob, would it be written with the rune Uruz or Ansuz on the end, or is it open to interpretation to the individual (for example the spellings of the Scottish clan name Macbeth/McBeath)?

Sorry for such a barrage of questions, but I am truly fascinated by them and their history!

Thank you very much for taking the time to read and answer my questions.

Kind regards,

Jake

Why such or such form of a rune was in use in such or such sircumstances, is a very complex question. I don’t think the appearance of the star-shaped gēr rune on the artifacts is to be connected with the semantics of the ‘gift’. As for the bind runes, they actually worked as typographic ligatures, the runes being usually combined because of the lack of space. A look at the actual inscriptions will answer a lot of questions right away.

Runic inscriptions never avoid using the same rune twice in a word. Viking Age Younger Futhark inscriptions usually do not use two identical runes in a row. Anglo-Saxon runic inscriptions allow even that.

When you write about the name Helene, you write about ehwaz and hagall. Ehwaz is the name of the Elder Futhark rune. Hagall is the name of the Younger Futhark rune. If you want to write your text in the Anglo-Saxon runes, you should not confound runic alphabets. Also, I don’t see why Helene should be turned into Helena to be written in runes.

Hi Tim

Just wanted to point out that Edred Thursson and Steven Flowers is the same person

Thank you, Andy.

I was wondering how accurate is this translation? Want to get the girlfriend’s name tattooed in Viking Runes. I don’t want to be walking around with something written that not what it supposed to mean

Hello Alan. Anglo-Saxon runes have nothing to do with Vikings.

I am wondering what a good starter book on runes is? I bought and Edred Thorsen and a Steven Flowers book. Steven flowers advised that Edred Thorsen would make an important companion book/writer without actually divulging anywhere in either publication that he is Edred. Kind of made me a bit distrustful of his intentions in the books if he doesn’t bring that piece of information up. Only found about it while trying to find other books on web. So. You’re Viking runes. You should be able to advise. Tim

Hello Tim. I like very much books by R. I. Page. His Introduction to English Runes might be a very good choice.